Art Blakey

- Genre:

- Jazz

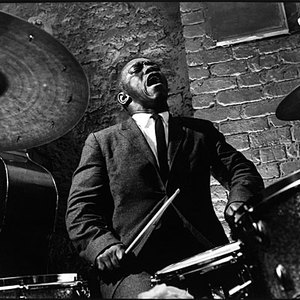

Arthur "Art" Blakey (October 11, 1919 ? October 16, 1990), also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina, was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. Along with Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, he was one of the inventors of the modern bebop style of drumming. He is known as a powerful musician and a vital groover; his brand of bluesy, funky hard bop was and continues to be profoundly influential on mainstream jazz.

Along with Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, he was one of the inventors of the modern bebop style of drumming. He is known as a powerful musician and a vital groover; his brand of bluesy, funky hard bop was and continues to be profoundly influential on mainstream jazz. For more than 30 years his band the Jazz Messengers included many young musicians who went on to become prominent names in jazz. The band's legacy is thus not only known for the often exceptionally fine music it produced, but as a proving ground for several generations of jazz musicians; Blakey's groups are matched only by those of Miles Davis in this regard. He was a member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Legendary jazz drummer Art Blakey (1919-1990) is best known for the band he led, known as Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, which over the course of thirty years included some of the most prominent jazz musicians of the day -- including Clifford Brown, Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, Wynton Marsalis and Branford Marsalis.

Blakey was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. By the time he was a teenager he was playing the piano full-time, leading a commercial band. Shortly afterwards, he taught himself to play the drums in the aggressive swing style of Chick Webb, Sid Catlett and Ray Bauduc. He joined Mary Lou Williams as a drummer for an engagement in New York in autumn 1942. He then toured with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra (1943?4). During his years with Billy Eckstine's big band (1944?7) Blakey became associated with the modern-jazz movement, along with his fellow band members Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Fats Navarro and others.[4]

In 1947 Blakey organized the Seventeen Messengers, a rehearsal band, and recorded with an octet called the Jazz Messengers. He claimed that he then travelled to Africa. Unfortunately, no documentation has been uncovered that supports this claim. In the early 1950s he performed and broadcast with such musicians as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Clifford Brown, and particularly with Horace Silver, his kindred musical spirit of this time. Blakey and Silver recorded together on several occasions, including the album A Night at Birdland (1954, BN), having formed in 1953 a cooperative group with Hank Mobley and Kenny Dorham, retaining the name Jazz Messengers. By 1956 Silver had left and the leadership of this important band passed to Blakey, and he remained associated with it until his death. It was the archetypal hard-bop group of the late 1950s, playing a driving, aggressive extension of bop with pronounced blues roots. Over the years the Jazz Messengers served as a springboard for young jazz musicians such as Donald Byrd, Johnny Griffin, Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Keith Jarrett, Chuck Mangione, Woody Shaw, JoAnne Brackeen and Wynton Marsalis. Blakey also made a world tour in 1971?2 with the Giants of Jazz (with Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk and Al McKibbon). [4]

From his earliest recording sessions with Eckstine, and particularly in his historic sessions with Monk in 1947, Blakey exuded power and originality, creating a dark cymbal sound punctuated by frequent loud snare- and bass-drum accents in triplets or cross-rhythms. Although Blakey discouraged comparison of his own music with African drumming, he adopted several African devices after his visit in 1948?9, including rapping on the side of the drum and using his elbow on the tom-tom to alter the pitch. His much-imitated trademark, the forceful closing of the hi-hat on every second and fourth beat, was part of his style from 1950 to '51. A loud and domineering drummer, Blakey also listened and responded to his soloists. His contribution to jazz as a discoverer and molder of young talent over three decades was no less significant than his very considerable innovations on his instrument.

In the 1940s, Blakey was a member of bands led by Mary Lou Williams, Fletcher Henderson, and Billy Eckstine. He converted to Islam during a visit to West Africa in the late 1940s and took the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina (which led to the nickname "Bu"). By the late forties and early fifties, Blakey was backing musicians such as Miles Davis, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk ? he is often considered to have been Monk's most empathetic drummer, and he played on both Monk's first recording session as a leader (for Blue Note Records in 1947) and his final one (in London in 1971), as well as many in between.

Up to the 1960s Blakey also recorded as a sideman with many other musicians: Jimmy Smith, Herbie Nichols, Cannonball Adderley, Grant Green, and Jazz Messengers graduates Lee Morgan and Hank Mobley, amongst many others. However, after the mid-1960s he mostly concentrated on his own work as a leader.

The origins of the Messengers are in a series of groups led or co-led by Blakey and pianist Horace Silver, though the name was not used on the earliest of their recordings. The most celebrated of these early records (credited to "The Art Blakey Quintet"), is A Night at Birdland from February 1954, one of the earliest commercially released "live" jazz records. This featured Silver, Blakey, the young trumpeter Clifford Brown, alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson and bassist Curly Russell. The "Jazz Messengers" name was first used on a 1954 recording nominally led by Silver, with Blakey, Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham and Doug Watkins ? the same quintet would record The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia the following year, still as a collective. Donald Byrd replaced Dorham, and the group recorded an album called simply The Jazz Messengers for Columbia Records in 1956. Blakey took over the group name when Silver left after the band's first year (taking Mobley, Byrd and Watkins with him to form a new quintet with a variety of drummers), and the band was known as "Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers" from then onwards.

From 1959 to 1961 the group featured Wayne Shorter on tenor saxophone, Jymie Merritt, Lee Morgan, and Bobby Timmons. The second line-up (1961?1964) was a sextet that added trombonist Curtis Fuller and replaced Morgan and Timmons with Freddie Hubbard and Cedar Walton, respectively. Shorter was the musical director of the group, and many of his original compositions such as "Lester Left Town" remained staples of Blakey's repertoire even after Shorter's departure. (Other players over the years made permanent marks on Blakey's repertoire ? Timmons, composer of "Dat Dere" and "Moanin'", Benny Golson, composer of "Along Came Betty" and "Are You Real", and, later, Bobby Watson.) Shorter's more experimental inclinations pushed the band at the time into an engagement with the 1960s "New Thing", as it was called: the influence of Coltrane's contemporary records on Impulse! is evident on Free For All (1964), often cited as the greatest document of the Shorter-era Messengers (and certainly one of the most fearsomely powerful examples of hard bop on record)

Blakey went on to record dozens of albums with a constantly changing group of Jazz Messengers ? he had a policy of encouraging young musicians: as he remarked on-mike on A Night at Birdland (1954): "I'm gonna stay with the youngsters. When these get too old I'll get some younger ones. Keeps the mind active." After weathering the fusion era in the 1970s with some difficulty (recordings from this period are less plentiful and include attempts to incorporate instruments like electric piano), Blakey's band got revitalized in the early 1980s with the advent of neotraditionalist jazz. Wynton Marsalis was for a time the band's trumpeter and musical director, and even after Marsalis's departure Blakey's band continued as a proving ground for many "Young Lions" like Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison and Kenny Garrett. Blakey continued performing and touring with the group into the late 1980s, and he died in 1990 of lung cancer in New York City, leaving behind a vast legacy and approach to jazz which is still the model for countless hard-bop players.

- Sort by

Holiday For Skins

- Year:

- 2011

- Tracks:

- 8

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

The Perfect Jazz Collectionthe Jazz Messengers

- Year:

- 2010

- Tracks:

- 12

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

The Early Years

- Year:

- 2010

- Tracks:

- 14

- Bitrate:

- 121 kbps

Paris Olympia

- Year:

- 2008

- Tracks:

- 7

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

Paris Jam Session

- Year:

- 2001

- Tracks:

- 4

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

Ken Burns Jazz: The Definitive Art Blakey

- Year:

- 2000

- Tracks:

- 9

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

A Night At Birdland

- Year:

- 1987

- Tracks:

- 6

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

Straight Ahead

- Year:

- 1981

- Tracks:

- 6

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

Anthenagin (Vinyl)

- Year:

- 1973

- Tracks:

- 6

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

The Giants Of Jazz - Recorded Live At The Victoria Theatre In London (Vinyl) CD2

- Year:

- 1971

- Tracks:

- 6

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps

Benny Golson 27

Benny Golson 27 Cedar Walton 33

Cedar Walton 33 Donald Byrd 53

Donald Byrd 53 Elvin Jones 34

Elvin Jones 34 Hank Mobley 58

Hank Mobley 58 Barney Wilen 7

Barney Wilen 7 Benny Green 11

Benny Green 11 Billy Eckstine 8

Billy Eckstine 8 Bobby Watson 12

Bobby Watson 12 Branford Marsalis 13

Branford Marsalis 13 Carlos Garnett 6

Carlos Garnett 6 Charles Fambrough 5

Charles Fambrough 5 Chuck Mangione 43

Chuck Mangione 43 Donald Harrison 18

Donald Harrison 18 Eddie Henderson 22

Eddie Henderson 22 Jackie McLean 50

Jackie McLean 50 James Williams 7

James Williams 7 Joanne Brackeen 18

Joanne Brackeen 18 John Hicks 11

John Hicks 11 Johnny Griffin 18

Johnny Griffin 18 Kenny Dorham 24

Kenny Dorham 24 Lou Donaldson 50

Lou Donaldson 50 Sonny Stitt 55

Sonny Stitt 55 Terence Blanchard 18

Terence Blanchard 18 The Jazztet 10

The Jazztet 10 Thelonious Monk 97

Thelonious Monk 97 Wallace Roney 17

Wallace Roney 17 Wynton Marsalis 51

Wynton Marsalis 51 Buddy Rich 40

Buddy Rich 40 Cannonball Adderley 47

Cannonball Adderley 47 Charlie Parker 86

Charlie Parker 86 Charlie Watts 7

Charlie Watts 7 Chico Hamilton 28

Chico Hamilton 28 Clifford Brown 37

Clifford Brown 37 Dexter Gordon 104

Dexter Gordon 104 Horace Silver 40

Horace Silver 40 Jimmy Cobb 7

Jimmy Cobb 7 John Coltrane 237

John Coltrane 237 Kenny Clarke 7

Kenny Clarke 7 Max Roach 38

Max Roach 38 Miles Davis 295

Miles Davis 295 Philly Joe Jones 14

Philly Joe Jones 14 Roy Haynes 10

Roy Haynes 10