Bernie Green

- Genre:

- Easy Listening

- Meta style:

- Exotica/Lounge

- Style:

- Space Age Pop

1) Bernie Green's career embodies the contradictions of space age pop. On the one hand, here is a typical worker on the assembly line of studio music, taking on whatever job comes next: musical director for "The Garry Moore Show," leading the pit orchestra for years of Miss USA and Miss Universe pageants, or conducting the a marching band for an RCA album (a task Henry Mancini and Ray Martin also took on to pay the rent).

On the other hand, you have some of the most innovative and memorable recordings of the genre: More Than You Can Stand in Hi-Fi; Musically MAD; and Futura, perhaps the best of the consistently exceptional RCA Stereo Action series. It's a little like trying to resolve Mr. Stevens, the vice president of the Hartford Insurance Company with Wallace Stevens, the abstract impressionist poet.

Unlike Wallace Stevens, though, little record remains of Bernie Green's career. He studied music at New York University's College of Fine Arts, graduating in 1932. Green quickly slipped a foot in the door of radio, which was just entering its heyday, and he spent much of the next two decades working on various network shows. His radio career culminated with the job of musical director for the Henry Morgan Show, on which Green was given a regular three-minute spot each show. Green wrote both original pieces and adaptations for these spots. Several of these pieces would later appear on his More Than You Can Stand in Hi-Fi album.

He moved over to the television business in the early 1950s, again working as musical director for several very successful (Wally Cox's "Mr. Peepers" and "The Garry Moore Show") and several very unsuccessful ("Cool McCool" and "Zotz!") shows. He scored two films that compiled comedy bits from silent and early talking pictures: "30 Years of Fun" and "MGM's Big Parade of Comedy."

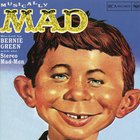

Although his own recordings are few, they are well worth seeking out. More Than You Can Stand in Hi-Fi is something of a parody of the craze among hi-fi buffs for unusual instrumentation and striking arrangements. Green took this approach beyond the limits of common sense, offering such items as Brahm's "Hungarian Rhapsody #2" as a solo piece for kettle drum and the "Minute Waltz" played by a sax quartet. As might be expected, Musically MAD, with Alfred E. Neumann grinning prominently on the cover, appeals to the eternally adolescent sense of humor with "Concerto for Two Hands," in which the melody is rendered through the old trick of squeezing your palms together to make farting noises. And Futura anticipates the work of Perrey and Kingsley with its use of "animated tape" and "tonalyzers." Green's striking interpretation of standards like "Under Paris Skies" led Hi Fi Magazine to comment,

The electronic music and musique concrete boys had better watch out: surely they've never appealed so provocatively or to so wide an audience as do the present sugar-coated experiments in and divertissements on the sound of the future.

Be prepared for a lengthy search and/or premium prices for these albums, though. I suspect all were released in minimum quantities and it appears that none has been reissued, although a few cuts from Futura can be heard on Irwin Chusid's three-CD anthology "History of Space Age Pop" on RCA (now, sadly, out of print).

2) Bennie Green was one of the few trombonists of the 1950s who played in a style not influenced by J.J. Johnson (Bill Harris was another). His witty sound and full tone looked backwards to the swing era yet was open to the influence of R&B. After playing locally in Chicago, he was with the Earl Hines Orchestra during 1942-1948 (except for two years in the military). Green gained some fame for his work with Charlie Ventura (1948-1950) before joining Earl Hines' small group (1951-1953). He then led his own group throughout the 1950s and '60s, using such sidemen as Cliff Smalls, Charlie Rouse, Eric Dixon, Paul Chambers, Louis Hayes, Sonny Clark, Gildo Mahones, and Jimmy Forrest. Green recorded regularly as a leader for Prestige, Decca, Blue Note, Vee-Jay, Time, Bethlehem, and Jazzland during 1951-1961, although only one further session (a matchup with Sonny Stitt on Cadet in 1964) took place. Bennie Green was with Duke Ellington for a few months in 1968-1969 and then moved to Las Vegas, where he spent his last years working in hotel bands, although he did emerge to play quite well at the 1972 Newport Jazz Festival and in New York jam sessions.

- Sort by

Musically Mad

- Year:

- 2010

- Tracks:

- 13

- Bitrate:

- 320 kbps